This project was funded through Museum of London Archaeology’s (MOLA) Impact Accelerator Creative Residencies grant and is a collaboration with geoarchaeologists Eduardo Machicado and David Humphreys.

I met Eduardo through my London Clay research and he piqued my interest by referring to traditional archeology as ‘mining’ - going in to look for very specific treasures, which we then extract - whereas geoarchaeology looks at the wider matrix; the context between archaeology and deep time. This got me thinking about archaeology in general and our relationship with what we dig out of the ground. Why are certain objects dug out of the ground deemed more interesting than others? And what does this say about society, particularly in the context of the Anthropocene?

David since shared a thought experiment with me, The Silurian Hypothesis, which poses the question; what if we are not the earth’s first civilisation? No one actually believes this, but it raises some interesting questions about how we interpret what we find in the earth’s crust and what we are leaving behind. Due to tectonic plate movements, the earth’s crust is apparently completely changed every 0.5 billion years, so actually pretty much nothing is left of the original crust. I always thought of the layers below us as fixed, but they are in constant (very slow) flux. With global warming, we are putting down geological markers, very similar to those at extreme times of change throughout the past few hundred million years. Our interpretation of those is based on very little evidence. How will our time be interpreted millions of years from now? What are we leaving behind?

We have had some interesting conversations about the Anthropocene and (hu)man’s place in the world. How everything is interconnected and ways of readdressing our western worldview, in which man is seen as somehow separate to nature and this formed the basis of our grants application. To jointly look at geological core samples and see what kinds of work could come of it. After a successful funding application, I was given a set of geological core samples from 4 different boreholes and the full geoarchaelogical records of borehole 2. I quickly begun to take these apart and experiment with the materials.

Above: Same materials at 0, 900 and 1150 degrees C.

One of the first things I did was to run the samples past Bente Sonne and Tracy Weston, a couple of glassblowers, to see how the materials would interact with glass. I am interested in the idea of adding clay to glass, rather than the other way around, which is the way that these two craft traditions merge.

I then ran the glass samples through the microscope at Natural History Museum to see whether anything interesting was happening at a microscopic level. Mostly bubbles and nothing very exciting, although they are very attractive. I like the little landscapes they make.

BH2

I have received a full log for borehole 2 (BH2), so will be focusing my efforts on this borehole. Whilst chewing my way through the report, trying to make sense of it, I started opening the samples to work out what they hold. The first 3.5 meters are made up almost entirely of clay, with a bit of building dust and modern debris. I am trying to work out how old it is and how it got to be there, but facts are remarkably hard to come by, because no one really bother looking into these things. It is a very interesting looking clay, a mixture of grey, orange and almost black. The outer circle is a different colour to the internal core, which I assume is due to oxygen coming into contact with the outer layer and changing the colour of the iron.

This ‘mottled’ effect comes out quite striking at low temperatures.

Eduardo and David have very kindly gone through the process for treating the samples from a geoarcheological point of view. This includes powdering the samples and sifting them to create tiny particles, which can be used for analysis. I am interested in the process of breaking materials down into their smallest parts and then re-animating them. This is very similar to how a ceramicist might treat their raw materials to make glazes and slips. In fact their equipment is very similar to mine - a mortar and pestle and a few fine sieves. One of the main approaches to analysis is to determine whether there are spikes in the magnetism of their materials, as this would signify the presence of fire. Heat changes the magnetism of materials, which is definitely something for my research. As an experiment, I have begun to add metal dust to my materials to play around with magnetism.

During conversations, I have become particularly interested in the concept of technosoils, soils layers in urban areas, defined by the presence of human-made artefacts, and the relationship that it has to deep history and the far future. Technofossils, a term coined by Professor Jan Zalasiewicz and colleagues at the University of Leicester, considers the future of technosoils and describes the material footprints that humans will leave behind through their material goods. Globally, the majority of the objects that we create end up in a landfill. As a result of government legislation about how we should deal with our trash, landfills have become modern-day tombs that extend the time it takes for things to decay. Thus, the vast majority of our stuff will be hardened in another geological layer before having the opportunity to decompose and disappear. What novel geologies will the future hold? As dinosaur bones fossilise over time, so too will lounge chairs, ballpoint pens, safety pins, compressed media drives, cars, and so many other objects become archaeological artefacts.

I find this relationship between past, present and future fascinating. And it relates to my original idea of mining and value. The lasting impression that we will leave behind will be largely defined by our rubbish.

I have begun exploring ways of combining urban geology with man-made waste, looking at urban mining (using the city as a place for gathering of materials) and firing this at high temperature to create new materials. I have been photographing these pots through a microscope at the natural history museum. These image also feed into my ongoing Moments in Time project.

Really interesting things happen at this level, particularly when fired at above 1200 degrees. New bonds start to form and things that look calm at the surface, show traces of chaos and extreme conditions when viewed up close. I like the way they look like the universe or recognisable structures. There is a very satisfying symmetry to it, a kind of feeling that everyone seem to have, that there are repetitions of structures within the micro and the macro.

At the moment, my approach is not a methodical ceramicist method, but rather a creative exploration of ‘what if’, and as such I am not creating glazes or engobes or even clay bodies. I am discovering some interesting material details though:

London clays tend to be stable and make beautiful, deep brown surfaces when fired high. Particularly more recent (holocene) clays get an almost metallic shine at 1200.

A bit of costume jewellery crystallising into unexpected shapes

Copper and brass integrate beautifully and make lovely greens and at a microscopic level they are really interesting. Shop bought copper oxide is quite dull and stable, whereas found copper oxide - and copper dust etc. make beautiful patterns. They look the same on the surface, but when you delve in, they are completely different. The images above show ceramic copper oxide on the left and electrical wiring on the right.

Iron and metal mixes are extremely volatile and keep changing. Especially coins and cheap jewellery are made of strange alloys, which grow into almost crystal like structures that are very unstable.

Some materials are completely unpredictably beautiful - the image on the left shows a lump of asphalt found in a core sample, the one on the right a bit of brass chain and London clay.

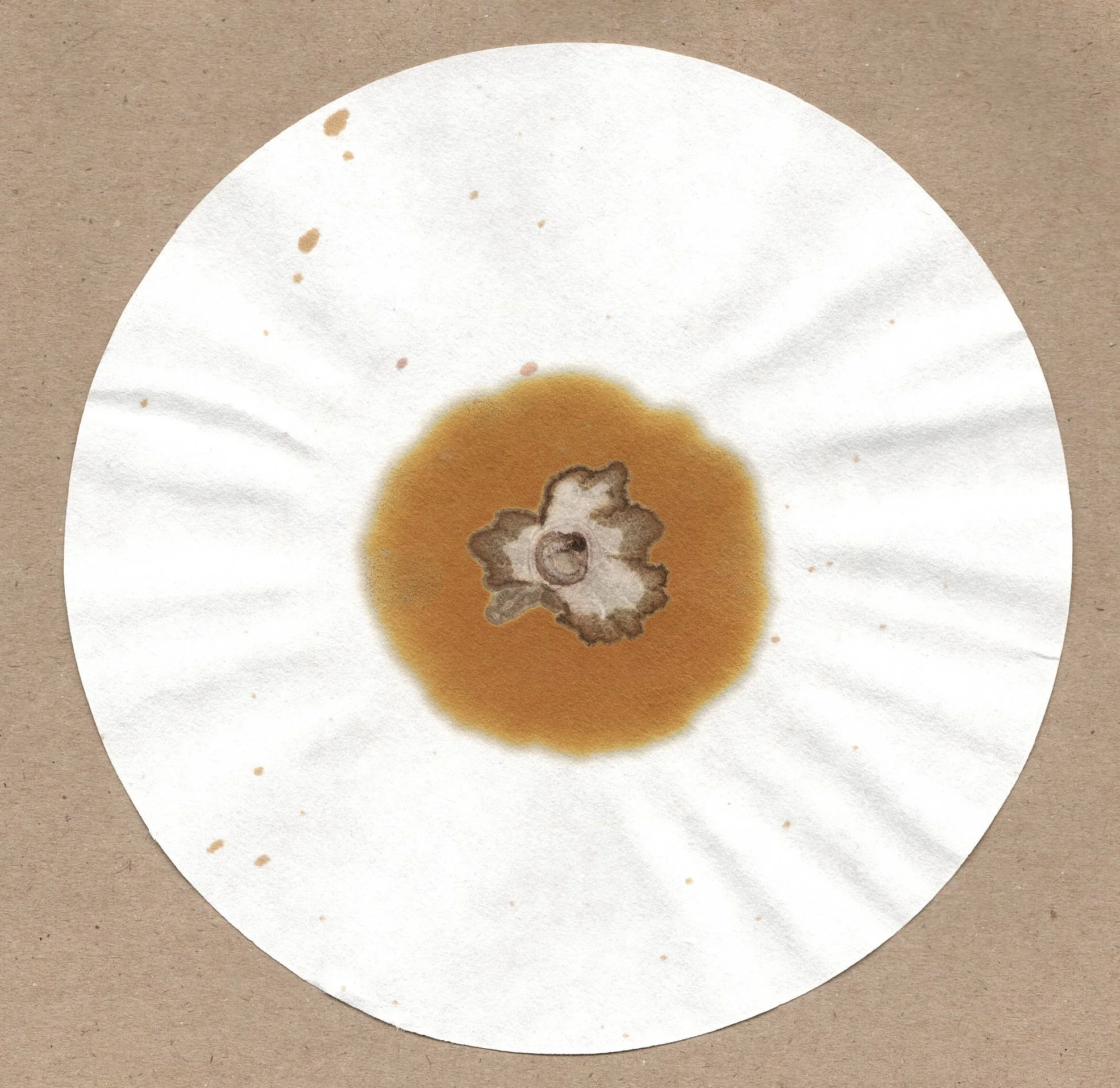

I have been trying my hand at soil chromatography of the different geology samples with varying degrees of success. There is something interesting about eking out the the clay secrets that appeals to me and they can be extremely striking images.